In part one of this two-part series, Rob Arnott, the founder and chairman of Research Affiliates, and colleagues Lillian Wu, vice president of the firm’s European business strategy, and Brian Cornell, professor of finance at UCLA, explore the astronomical valuations of electric vehicle companies and how these compare to traditional automotive stocks.

Key points:

- The “big market delusion” is when all firms in an evolving industry rise together, although as competitors ultimately some will win, and some will lose.

- The electric vehicle industry, with its astronomical growth in market-cap over the 12 months ending 31 January 2021, is a prime example of a big market delusion.

- In the highly competitive and capital-intensive auto industry, the January 2021 valuations of electric vehicle manufacturers are simply not sustainable over the long term.

Big markets have a special allure for investors. They offer the promise of another Apple [AAPL], Google [GOOGL], or Microsoft [MSFT]. But big markets also bring with them the threat of what Cornell and Damodaran (2020) call “the big market delusion”.

Big market delusions generally begin with innovation or disruption that opens a new market, such as cannabis, or reinvents an old one, such as advertising. The hallmark of a big market delusion is when all the firms in the evolving industry rise together even though they are often direct competitors.

Investors become so enthusiastic that each firm is priced as if it will be a major winner in the evolving big market despite the fact this is a fallacy of composition: the sum of the parts cannot be greater than the whole.

The lesson of the airline industry

An example of a big market delusion is the invention and development of aircraft. The development of the airplane was one of the great technological innovations of the early 20th century. In the years that followed, affordable air travel and transport revolutionised the way people lived and interacted as well as altered global commerce and trade. Air transport became a huge business, but airlines did not necessarily provide a wealth bonanza for investors.

From the beginning, the air travel business has been capital intensive and highly competitive. During good times, new airlines emerged and drove down profits. During bad times, many less well-capitalised companies folded. Over the course of the last century, virtually every company in the business either failed or merged into a larger airline, most of which also collapsed.

The simple fact, as Warren Buffett so cleverly stated, is that technology does not translate into great fortunes for investors unless it is associated with barriers to entry that allow a company to earn returns significantly in excess of the cost of capital for an extended period.

Of course, Apple, Google, and Facebook [FB] are well-known examples of such technological success, but they are the exception rather than the rule. For a host of complicated reasons, these companies have been able to build moats, or barriers to entry, around their businesses. They also benefit from the fact their products can be produced with limited capital investment.

A lesson in the making?

Like airlines, the auto industry has historically been a competitive, capital-intensive business. For this reason, despite the global demand for their products, the traditional major auto manufacturers have tended on average to trade at book-to-market ratios near or below 1.0.

From an industry perspective, we have little reason to believe that a change in the propulsion system from internal combustion engines to electric motors should have a pronounced impact on market competition or on the total industry valuation of the companies.

We examine the recent growth in market value for the global auto industry, focusing on the largest public auto companies by market capitalisation. Over the three-year period ending 31 January 2021, the global auto industry gained 70% in market value, growing to $2.16trn.

Interestingly, auto industry total value declined for the first two years, 2018 and 2019, of the three-year period. Traditional automakers absorbed almost all of the decline in value, while the market value of electric vehicle (EV) specialists remained flat.

The year 2020 was a spectacular year for the auto industry in terms of valuation appreciation, as EV specialists became the market’s latest beloved companies and led a remarkable price run-up.

As of 31 January 2021, the total market value of the eight EV specialists in our universe was $1trn, after year-over-year growth of 618%, almost on par with the $1.1trn combined value of traditional automakers.

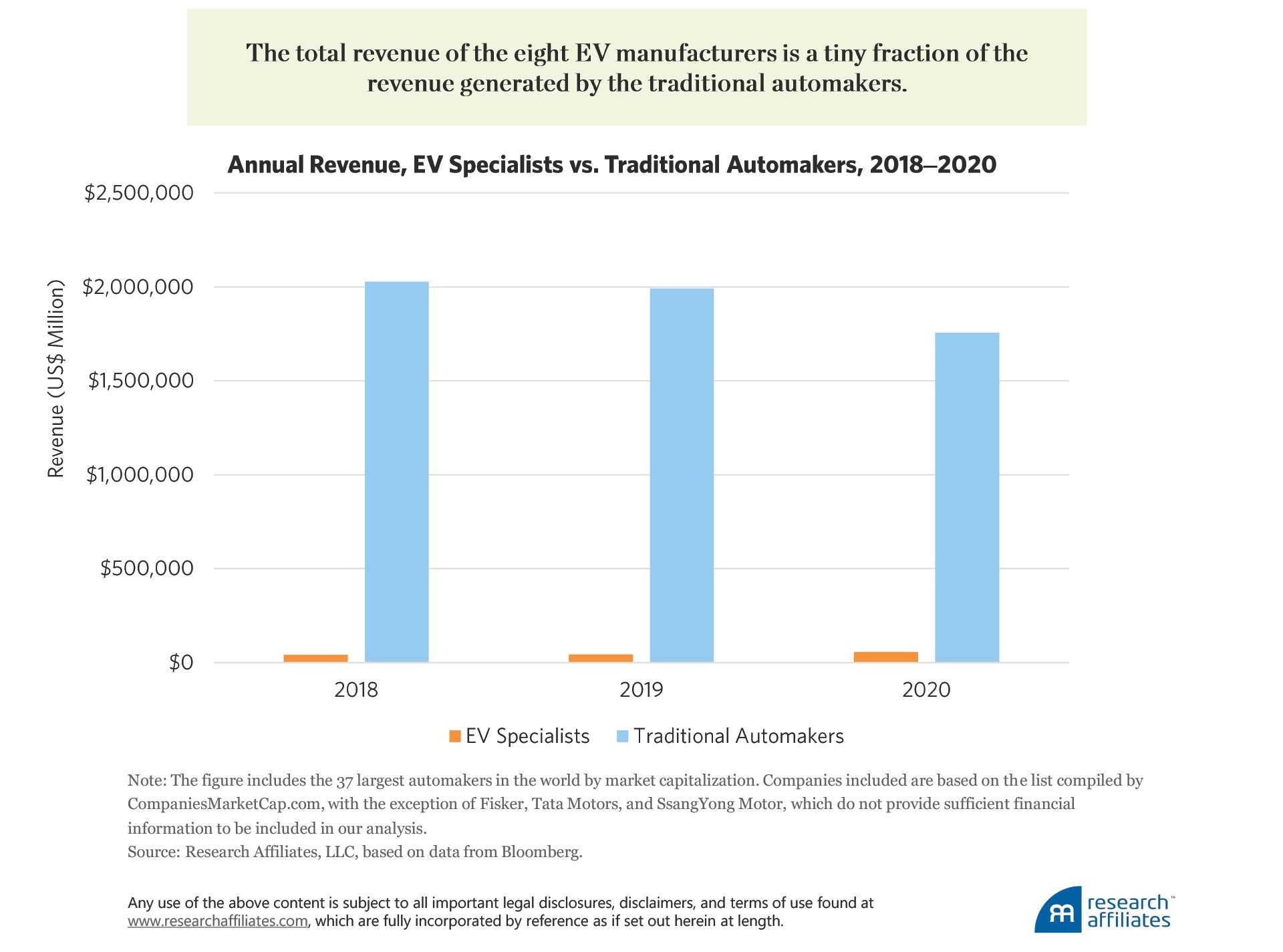

In contrast to their astounding growth in market value, EV specialists’ combined total revenues remain as they have over the last three years at only a tiny fraction of the revenues generated by the traditional automakers: 1 to 42 on average over the three-year period. Furthermore, the entire industry’s total revenue fell in 2020 even as share prices skyrocketed.

Much of the increase in the industry’s market-cap was a result of the massive increase in Tesla’s [TSLA] market-cap. As of the end of January 2021, Tesla’s market capitalisation had risen to $752bn, placing it in the top 10 companies in the world by market value.

At that market capitalisation, Tesla accounted for about 75% of the total EV group’s market value and 35% of the market value of the entire auto industry. Such an immense market capitalisation makes sense only if the expectation is that Tesla will come to dominate the entire auto industry, not just the EV market.

Such an achievement requires that both Tesla’s brand and technology become so dominant that the company can earn profit margins that exceed those of Ferrari [RACE] on a level of production exceeding that of Toyota [TM]. If that is the scenario reflected in Tesla’s price, it should also be reflected in the falling valuations of its competitors, including competing EV specialists, whose market share will presumptively decline in favour of Tesla — however, the reverse is true.

While Tesla’s stock price has been skyrocketing, the prices of competing EV firms have been too. Although the concurrent price increases of most conventional automakers could not be described as skyrocketing, they were rising handily, although a few did lose ground.

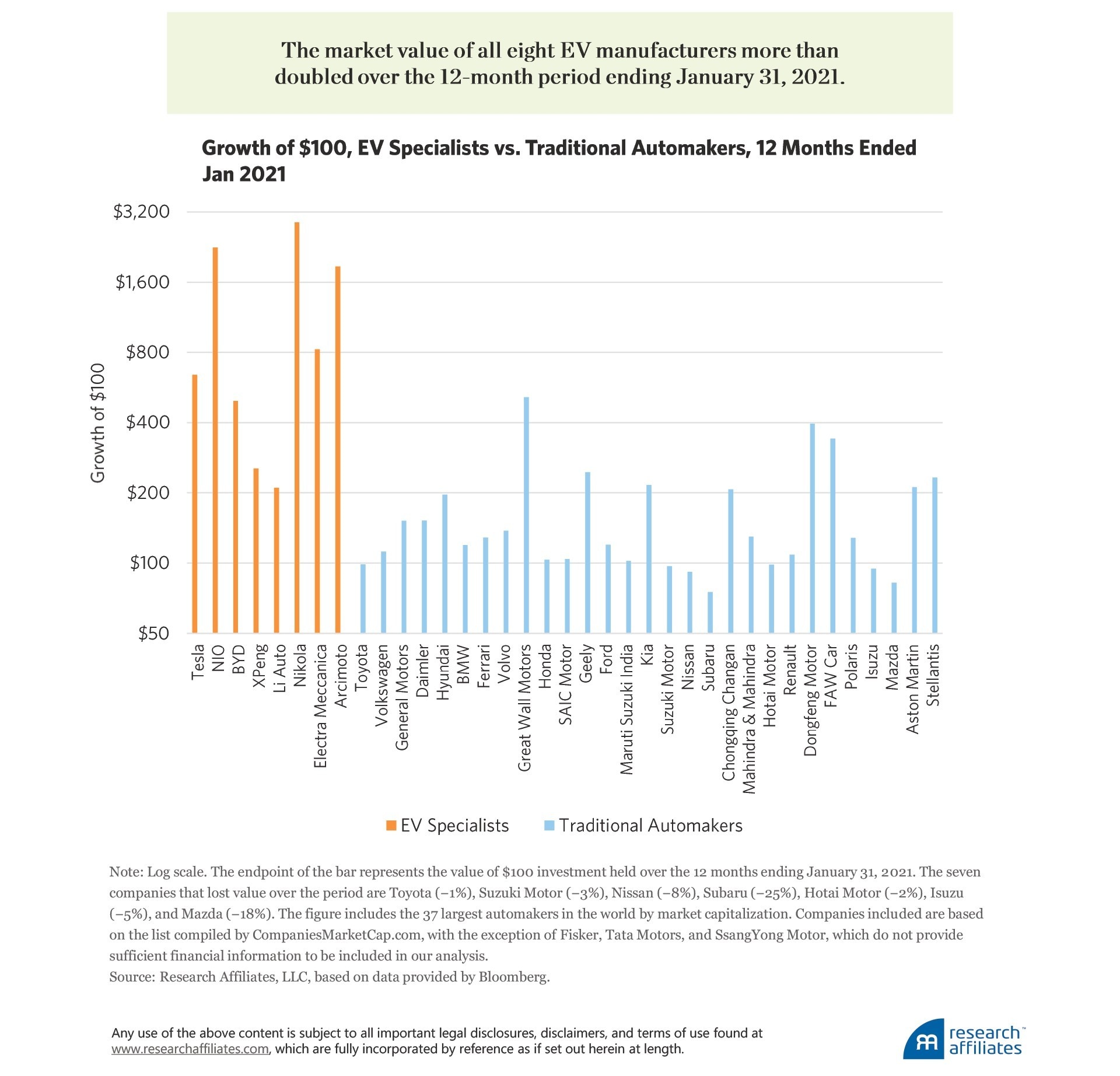

Let’s compare the growth of $100 over the 12 months ended 31 January 2021, if invested in each of the largest public auto companies by market capitalisation. Seven conventional automakers — Toyota, Suzuki Motor [7269], Nissan [NSANY], Subaru [FUJHY], Hotai Motor [2207], Isuzu [ISUZY] and Mazda [MSDAY] — lost market value (or more accurately did not fully recover losses from the COVID-19 crash), while the market value of eight traditional automakers more than doubled — Great Wall Motors [2333.HK], Geely [GELYF], Kia [00027], Chongqing Changan [000625.SZ], Dongfeng Motor [DNFGF], FAW Car [000800.SZ], Aston Martin [AML.L] and Stellantis [STLA].

The market value of all eight of the EV specialists more than doubled over the 12 months ending 31 January 2021, and the market value of three of these rose more than tenfold: $100 invested in Nikola [NKLA], a maker of zero-emission trucks with no clear plan as to when it would actually start selling trucks, grew by an astronomical 2800%; $100 invested in Nio [NIO], a Chinese EV start-up once near ruin, climbed 2150%; and $100 invested in Arcimoto [FUV], the maker of three-wheeler EVs, rose by 1770%.

The market values of two Chinese EV specialists, Li Auto [LI] and XPeng [XPEV], first listed on the New York Stock Exchange in July and August 2020, respectively, jumped 110% and 150%, respectively, by the end of January 2021. The valuations of three Chinese traditional auto companies — Great Wall Motors, ChongQing ChangAn, and FAW Car — rose solely on the basis of their stated commitment to the EV market.

When we exclude Tesla from the EV specialist group’s $1trn market-cap at end-January 2021, the combined market value of the seven other EV companies is $268bn, one-third Tesla’s value.

What could we buy for $268bn? We could buy not only Toyota — the largest traditional automaker by market capitalisation ($228bn at end of January 2021) and the most profitable automaker — but also Ferrari, the automaker with the highest profit margin.

$268bn is also the approximate market capitalisation of all major German automakers — Volkswagen [VOW.DE], Daimler [DAI.DE], and BMW [BMW.DE] — which together account for 17.6% of global auto market sales.

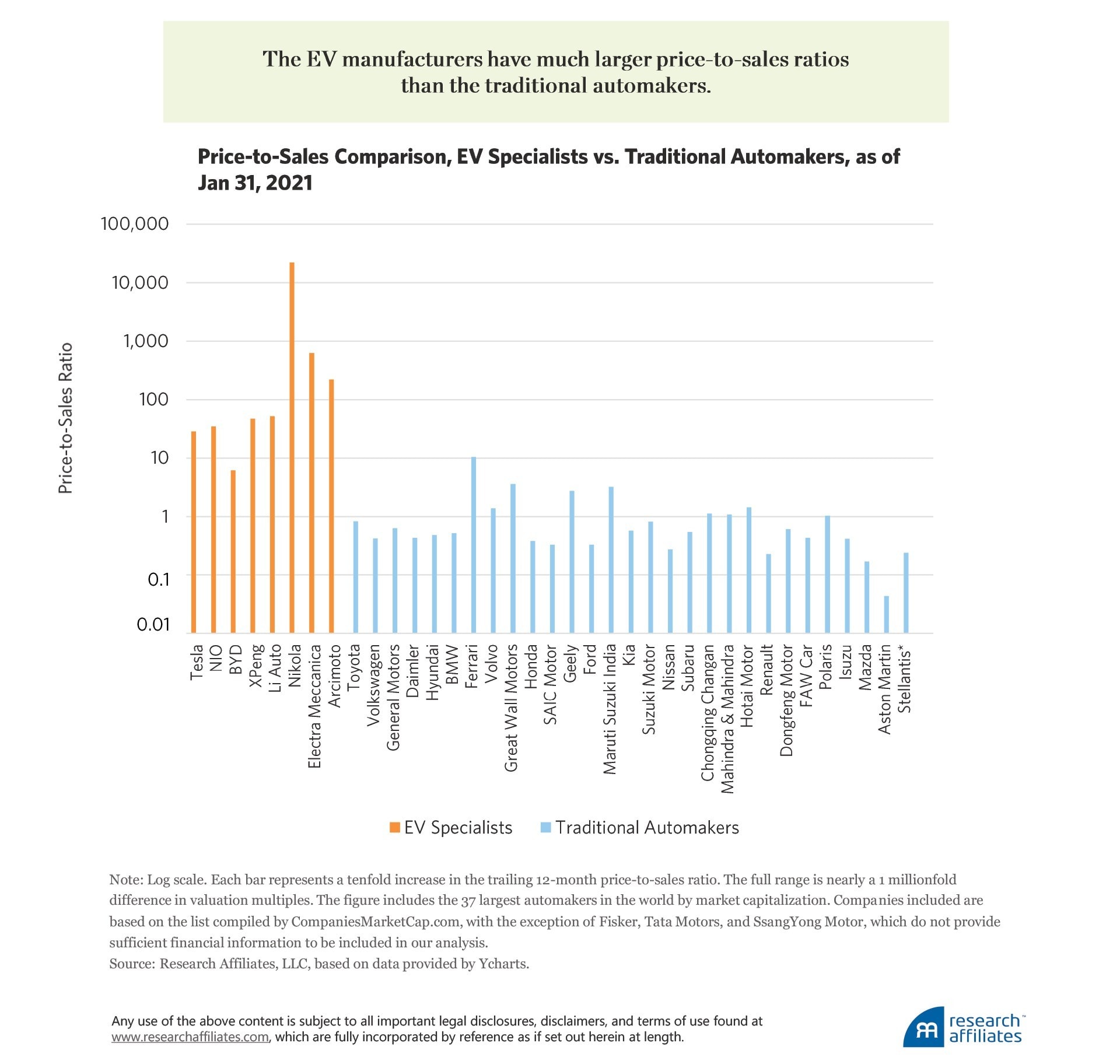

Exploding market value naturally leads to astronomically high valuation metrics. We compare the trailing 12-month price-to-sales ratio (P/S) for the 37 automakers in our analysis.

Due to the massive price-to-sales ratios of the new EV manufacturers, we use a logarithmic scale. For instance, Tesla is valued at 28 times its 2020 sales — a far stretch compared to the average P/S of 1.1 of the traditional automakers.

The pricing delusion is not exclusive to Tesla. In fact, Tesla’s valuation multiple of sales is only a fraction of the multiple of some of its competitors. Nicola Motor, founded in 2015, with near-zero revenues and no actual production to date, is priced at 22,000 times sales, and profits are, of course, nowhere in sight.

ElectraMeccanica [SOLO], also founded in 2015, the first maker of the electric three-wheeler, is priced at 600 times sales. Even new entrants XPeng and Li Auto are respectively priced at 47 times and 52 times sales, nearly twice the valuation multiple of Tesla.

All of these companies are priced as if they are going to be huge winners, but they are competitors! They cannot all assume dominant market share in the years ahead!

This article was originally published on the Research Affiliates website. Part two will discuss what led to the recent market competition among electric vehicle companies.

Disclaimer Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

CMC Markets is an execution-only service provider. The material (whether or not it states any opinions) is for general information purposes only, and does not take into account your personal circumstances or objectives. Nothing in this material is (or should be considered to be) financial, investment or other advice on which reliance should be placed. No opinion given in the material constitutes a recommendation by CMC Markets or the author that any particular investment, security, transaction or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person.

The material has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research. Although we are not specifically prevented from dealing before providing this material, we do not seek to take advantage of the material prior to its dissemination.

CMC Markets does not endorse or offer opinion on the trading strategies used by the author. Their trading strategies do not guarantee any return and CMC Markets shall not be held responsible for any loss that you may incur, either directly or indirectly, arising from any investment based on any information contained herein.

*Tax treatment depends on individual circumstances and can change or may differ in a jurisdiction other than the UK.

Continue reading for FREE